Data Wrangling and Analyses with Tidyverse

Last updated on 2026-01-27 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I manipulate data frames without repeating myself?

Objectives

- Explain the basic principle of tidy datasets

- Be able to load a tabular dataset using base R functions

- Describe what the

dplyrpackage in R is used for. - Apply common

dplyrfunctions to manipulate data in R. - Employ the ‘pipe’ operator to link together a sequence of functions.

- Employ the ‘mutate’ function to apply other chosen functions to existing columns and create new columns of data.

- Employ the ‘split-apply-combine’ concept to split the data into groups, apply analysis to each group, and combine the results.

Working with spreadsheets (tabular data)

A substantial amount of the data we work with in genomics will be tabular data, this is data arranged in rows and columns - also known as spreadsheets. We could write a whole lesson on how to work with spreadsheets effectively (actually we did). For our purposes, we want to remind you of a few principles before we work with our first set of example data:

1) Keep raw data separate from analyzed data

This is principle number one because if you can’t tell which files are the original raw data, you risk making some serious mistakes (e.g. drawing conclusion from data which have been manipulated in some unknown way).

2) Keep spreadsheet data Tidy

The simplest principle of Tidy data is that we have one row in our spreadsheet for each observation or sample, and one column for every variable that we measure or report on. As simple as this sounds, it’s very easily violated. Most data scientists agree that significant amounts of their time is spent tidying data for analysis. Read more about data organization in our lesson and in this paper.

3) Trust but verify

Finally, while you don’t need to be paranoid about data, you should have a plan for how you will prepare it for analysis. This a focus of this lesson. You probably already have a lot of intuition, expectations, assumptions about your data - the range of values you expect, how many values should have been recorded, etc. Of course, as the data get larger our human ability to keep track will start to fail (and yes, it can fail for small data sets too). R will help you to examine your data so that you can have greater confidence in your analysis, and its reproducibility.

Tip: Keep your raw data separate

When you work with data in R, you are not changing the original file

you loaded that data from. This is different than (for example) working

with a spreadsheet program where changing the value of the cell leaves

you one “save”-click away from overwriting the original file. You have

to purposely use a writing function (e.g. write.csv()) to

save data loaded into R. In that case, be sure to save the manipulated

data into a new file. More on this later in the lesson.

Base R (without additional packages) has a way of subsetting using brakets, which is handy, but it can be cumbersome and difficult to read, especially for complicated operations.

Luckily, the dplyr

package provides a number of very useful functions for manipulating data

frames (aka spreadsheets or tables of data) in a way that will reduce

repetition, reduce the probability of making errors, and probably even

save you some typing. As an added bonus, you might even find the

dplyr grammar easier to read.

Here we’re going to cover some of the most commonly used functions as

well as using pipes (%>%) to combine them:

glimpse()select()filter()group_by()summarize()mutate()-

inner_join(),full_join(),left_join(),right_join() - Extra -

pivot_longerandpivot_wider

Packages in R are sets of additional functions that let you do more

stuff in R. The functions we’ve been using, like str(),

come built into R; packages give you access to more functions. You need

to install a package and then load it to be able to use it.

R

install.packages("dplyr") ## installs dplyr package

install.packages("tidyr") ## installs tidyr package

install.packages("ggplot2") ## installs ggplot2 package

install.packages("readr") ## install readr package

Tip: Installing packages

It may be temping to install the tidyverse package, as

it contains many useful collection of packages for this lesson and

beyond. However, when teaching or following this lesson, we advise that

participants install dplyr, readr,

ggplot2, and tidyr individually as shown

above. Otherwise, a substaial amount of the lesson will be spend waiting

for the installation to complete.

You might get asked to choose a CRAN mirror – this is asking you to choose a site to download the package from. The choice doesn’t matter too much; I’d recommend choosing the RStudio mirror.

R

library("dplyr") ## loads in dplyr package to use

library("tidyr") ## loads in tidyr package to use

library("ggplot2") ## loads in ggplot2 package to use

library("readr") ## load in readr package to use

You only need to install a package once per computer, but you need to load it every time you open a new R session and want to use that package.

What is dplyr?

The package dplyr is a fairly new (2014) package that

tries to provide easy tools for the most common data manipulation tasks.

This package is also included in the tidyverse package,

which is a collection of eight different packages (dplyr,

ggplot2, tibble, tidyr,

readr, purrr, stringr, and

forcats). It is built to work directly with data frames.

The thinking behind it was largely inspired by the package

plyr which has been in use for some time but suffered from

being slow in some cases.dplyr addresses this by porting

much of the computation to C++. An additional feature is the ability to

work with data stored directly in an external database. The benefits of

doing this are that the data can be managed natively in a relational

database, queries can be conducted on that database, and only the

results of the query returned.

This addresses a common problem with R in that all operations are conducted in memory and thus the amount of data you can work with is limited by available memory. The database connections essentially remove that limitation in that you can have a database that is over 100s of GB, conduct queries on it directly and pull back just what you need for analysis in R.

Importing tabular data into R

There are several ways to import data into R. We will start loading

our data using the tidyverse package called readr and a

function called read_csv()

Exercise: Review the arguments of the

read_csv() function

Before using the read_csv() function, use R’s

help feature to answer the following questions.

Hint: Entering ‘?’ before the function name and then running

that line will bring up the help documentation. Also,

read_csv() is part of a family of functions for reading in

data called read_delim() so you will need to look for the

help page for read_delim() instead. When reading this

particular help be careful to pay attention to the ‘read_csv’ expression

under the ‘Usage’ heading. Other answers will be in the ‘Arguments’

heading.

What is the default parameter for ‘col_names’ in the

read_csv()function?What argument would you have to change to read a file that was delimited by semicolons (;) rather than commas?

What argument would you have to change to read skip commented lines (starting with #) at the beginning of a file (like our VCF file)? Hint: There are a couple of different possible answers to this question.

What argument would you have to change to read in only the first 10,000 rows of a very large file?

The

read_csv()function has the argument ‘col_names’ set to TRUE by default, this means the function always assumes the first row is header information, (i.e. column names)The

read_csv()function has the argument ‘delim’ which allows you to change the delimiter (aka separator) between columns. The function assumes commas are used as delimiters, as you would expect. Changing this parameter (e.g.delim=";") would now interpret semicolons as delimiters.To skip commented lines at the beginning of a file, there are a couple options. If the number of lines is consistent, we can use the

skipargument, for example,skip = 3will skip the first 3 lines of the file and then start reading in the header and data starting on line

- If the commented lines use a consistent delimeter (like #) we can

instead use the

commentargument, which skips any information after the charcter given. In this examplecomment = '#'will ignore lines starting with the hashtag/pound symbol. Note if you use both, skip will be executed first and then comment.

- You can set

n_maxto a numeric value (e.g.n_max=10000) to choose how many rows of a file you read in. This may be useful for very large files where not all the data is needed to test some data cleaning steps you are applying.

Hopefully, this exercise gets you thinking about using the provided help documentation in R. There are many arguments that exist, but which we wont have time to cover. Look here to get familiar with functions you use frequently, you may be surprised at what you find they can do.

Loading .csv files in tidy style

Now let’s load our vcf .csv file using read_csv():

OUTPUT

Rows: 801 Columns: 29

── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Delimiter: ","

chr (7): sample_id, CHROM, REF, ALT, DP4, Indiv, gt_GT_alleles

dbl (16): POS, QUAL, IDV, IMF, DP, VDB, RPB, MQB, BQB, MQSB, SGB, MQ0F, AC, ...

num (1): gt_PL

lgl (5): ID, FILTER, INDEL, ICB, HOB

ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.Taking a quick look at data frames

Similar to str(), which comes built into R,

glimpse() is a dplyr function that (as the

name suggests) gives a glimpse of the data frame.

OUTPUT

Rows: 801

Columns: 29

$ sample_id <chr> "SRR2584863", "SRR2584863", "SRR2584863", "SRR2584863", …

$ CHROM <chr> "CP000819.1", "CP000819.1", "CP000819.1", "CP000819.1", …

$ POS <dbl> 9972, 263235, 281923, 433359, 473901, 648692, 1331794, 1…

$ ID <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ REF <chr> "T", "G", "G", "CTTTTTTT", "CCGC", "C", "C", "G", "ACAGC…

$ ALT <chr> "G", "T", "T", "CTTTTTTTT", "CCGCGC", "T", "A", "A", "AC…

$ QUAL <dbl> 91.0000, 85.0000, 217.0000, 64.0000, 228.0000, 210.0000,…

$ FILTER <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ INDEL <lgl> FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, TR…

$ IDV <dbl> NA, NA, NA, 12, 9, NA, NA, NA, 2, 7, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

$ IMF <dbl> NA, NA, NA, 1.000000, 0.900000, NA, NA, NA, 0.666667, 1.…

$ DP <dbl> 4, 6, 10, 12, 10, 10, 8, 11, 3, 7, 9, 20, 12, 19, 15, 10…

$ VDB <dbl> 0.0257451, 0.0961330, 0.7740830, 0.4777040, 0.6595050, 0…

$ RPB <dbl> NA, 1.000000, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 0.900802, …

$ MQB <dbl> NA, 1.0000000, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 0.1501340…

$ BQB <dbl> NA, 1.000000, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 0.750668, …

$ MQSB <dbl> NA, NA, 0.974597, 1.000000, 0.916482, 0.916482, 0.900802…

$ SGB <dbl> -0.556411, -0.590765, -0.662043, -0.676189, -0.662043, -…

$ MQ0F <dbl> 0.000000, 0.166667, 0.000000, 0.000000, 0.000000, 0.0000…

$ ICB <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ HOB <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ AC <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ AN <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ DP4 <chr> "0,0,0,4", "0,1,0,5", "0,0,4,5", "0,1,3,8", "1,0,2,7", "…

$ MQ <dbl> 60, 33, 60, 60, 60, 60, 60, 60, 60, 60, 25, 60, 10, 60, …

$ Indiv <chr> "/home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned…

$ gt_PL <dbl> 1210, 1120, 2470, 910, 2550, 2400, 2080, 2550, 11128, 19…

$ gt_GT <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ gt_GT_alleles <chr> "G", "T", "T", "CTTTTTTTT", "CCGCGC", "T", "A", "A", "AC…In the above output, we can already gather some information about

variants, such as the number of rows and columns, column

names, type of vector in the columns, and the first few entries of each

column. Although what we see is similar to outputs of

str(), this method gives a cleaner visual output.

Selecting columns and filtering rows

To select columns of a data frame, use select(). The

first argument to this function is the data frame

(variants), and the subsequent arguments are the columns to

keep.

R

select(variants, sample_id, REF, ALT, DP)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 801 × 4

sample_id REF ALT DP

<chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 SRR2584863 T G 4

2 SRR2584863 G T 6

3 SRR2584863 G T 10

4 SRR2584863 CTTTTTTT CTTTTTTTT 12

5 SRR2584863 CCGC CCGCGC 10

6 SRR2584863 C T 10

7 SRR2584863 C A 8

8 SRR2584863 G A 11

9 SRR2584863 ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAG ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCC… 3

10 SRR2584863 AT ATT 7

# ℹ 791 more rowsTo select all columns except certain ones, put a “-” in front of the variable to exclude it.

R

select(variants, -CHROM)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 801 × 28

sample_id POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

<chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR2584863 9972 NA T G 91 NA FALSE NA NA 4

2 SRR2584863 263235 NA G T 85 NA FALSE NA NA 6

3 SRR2584863 281923 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA 10

4 SRR2584863 433359 NA CTTTTTTT CTTT… 64 NA TRUE 12 1 12

5 SRR2584863 473901 NA CCGC CCGC… 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9 10

6 SRR2584863 648692 NA C T 210 NA FALSE NA NA 10

7 SRR2584863 1331794 NA C A 178 NA FALSE NA NA 8

8 SRR2584863 1733343 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 11

9 SRR2584863 2103887 NA ACAGCCA… ACAG… 56 NA TRUE 2 0.667 3

10 SRR2584863 2333538 NA AT ATT 167 NA TRUE 7 1 7

# ℹ 791 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>, MQSB <dbl>,

# SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>, AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>,

# MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>, gt_GT_alleles <chr>dplyr also provides useful functions to select columns

based on their names. For instance, ends_with() allows you

to select columns that ends with specific letters. For instance, if you

wanted to select columns that end with the letter “B”:

R

select(variants, ends_with("B"))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 801 × 8

VDB RPB MQB BQB MQSB SGB ICB HOB

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl>

1 0.0257 NA NA NA NA -0.556 NA NA

2 0.0961 1 1 1 NA -0.591 NA NA

3 0.774 NA NA NA 0.975 -0.662 NA NA

4 0.478 NA NA NA 1 -0.676 NA NA

5 0.660 NA NA NA 0.916 -0.662 NA NA

6 0.268 NA NA NA 0.916 -0.670 NA NA

7 0.624 NA NA NA 0.901 -0.651 NA NA

8 0.992 NA NA NA 1.01 -0.670 NA NA

9 0.902 NA NA NA 1 -0.454 NA NA

10 0.568 NA NA NA 1.01 -0.617 NA NA

# ℹ 791 more rowsChallenge

Create a table that contains all the columns with the letter “i” and

column “POS”, without columns “Indiv” and “FILTER”. Hint: look at for a

function called contains(), which can be found in the help

documentation for ends with we just covered (?ends_with).

Note that contains() is not case sensistive.

R

# First, we select "POS" and all columns with letter "i". This will contain columns Indiv and FILTER.

variants_subset <- select(variants, POS, contains("i"))

# Next, we remove columns Indiv and FILTER

variants_result <- select(variants_subset, -Indiv, -FILTER)

variants_result

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 801 × 7

POS sample_id ID INDEL IDV IMF ICB

<dbl> <chr> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

1 9972 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

2 263235 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

3 281923 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

4 433359 SRR2584863 NA TRUE 12 1 NA

5 473901 SRR2584863 NA TRUE 9 0.9 NA

6 648692 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

7 1331794 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

8 1733343 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

9 2103887 SRR2584863 NA TRUE 2 0.667 NA

10 2333538 SRR2584863 NA TRUE 7 1 NA

# ℹ 791 more rowsChallenge (continued)

We can also get to variants_result in one line of

code:

R

variants_result <- select(variants, POS, contains("i"), -Indiv, -FILTER)

variants_result

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 801 × 7

POS sample_id ID INDEL IDV IMF ICB

<dbl> <chr> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

1 9972 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

2 263235 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

3 281923 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

4 433359 SRR2584863 NA TRUE 12 1 NA

5 473901 SRR2584863 NA TRUE 9 0.9 NA

6 648692 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

7 1331794 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

8 1733343 SRR2584863 NA FALSE NA NA NA

9 2103887 SRR2584863 NA TRUE 2 0.667 NA

10 2333538 SRR2584863 NA TRUE 7 1 NA

# ℹ 791 more rowsTo choose rows, use filter():

R

filter(variants, sample_id == "SRR2584863")

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 25 × 29

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR2584863 CP000819… 9.97e3 NA T G 91 NA FALSE NA NA

2 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.63e5 NA G T 85 NA FALSE NA NA

3 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.82e5 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA

4 SRR2584863 CP000819… 4.33e5 NA CTTT… CTTT… 64 NA TRUE 12 1

5 SRR2584863 CP000819… 4.74e5 NA CCGC CCGC… 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9

6 SRR2584863 CP000819… 6.49e5 NA C T 210 NA FALSE NA NA

7 SRR2584863 CP000819… 1.33e6 NA C A 178 NA FALSE NA NA

8 SRR2584863 CP000819… 1.73e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA

9 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.10e6 NA ACAG… ACAG… 56 NA TRUE 2 0.667

10 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.33e6 NA AT ATT 167 NA TRUE 7 1

# ℹ 15 more rows

# ℹ 18 more variables: DP <dbl>, VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>,

# MQSB <dbl>, SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>,

# AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>, MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>,

# gt_GT_alleles <chr>filter() will keep all the rows that match the

conditions that are provided. Here are a few examples:

R

# rows for which the reference genome has T or G

filter(variants, REF %in% c("T", "G"))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 340 × 29

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR25848… CP00… 9.97e3 NA T G 91 NA FALSE NA NA 4

2 SRR25848… CP00… 2.63e5 NA G T 85 NA FALSE NA NA 6

3 SRR25848… CP00… 2.82e5 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA 10

4 SRR25848… CP00… 1.73e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 11

5 SRR25848… CP00… 2.62e6 NA G T 31.9 NA FALSE NA NA 12

6 SRR25848… CP00… 3.00e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 15

7 SRR25848… CP00… 3.91e6 NA G T 225 NA FALSE NA NA 10

8 SRR25848… CP00… 9.97e3 NA T G 214 NA FALSE NA NA 10

9 SRR25848… CP00… 1.06e4 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 11

10 SRR25848… CP00… 6.40e4 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 18

# ℹ 330 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>, MQSB <dbl>,

# SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>, AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>,

# MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>, gt_GT_alleles <chr>R

# rows that have TRUE in the column INDEL

filter(variants, INDEL)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 101 × 29

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR25848… CP00… 4.33e5 NA CTTT… CTTT… 64 NA TRUE 12 1 12

2 SRR25848… CP00… 4.74e5 NA CCGC CCGC… 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9 10

3 SRR25848… CP00… 2.10e6 NA ACAG… ACAG… 56 NA TRUE 2 0.667 3

4 SRR25848… CP00… 2.33e6 NA AT ATT 167 NA TRUE 7 1 7

5 SRR25848… CP00… 3.90e6 NA A AC 43.4 NA TRUE 2 1 2

6 SRR25848… CP00… 4.43e6 NA TGG T 228 NA TRUE 10 1 10

7 SRR25848… CP00… 1.48e5 NA AGGGG AGGG… 122 NA TRUE 8 1 8

8 SRR25848… CP00… 1.58e5 NA GTTT… GTTT… 19.5 NA TRUE 6 1 6

9 SRR25848… CP00… 1.73e5 NA CAA CA 180 NA TRUE 11 1 11

10 SRR25848… CP00… 1.75e5 NA GAA GA 194 NA TRUE 10 1 10

# ℹ 91 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>, MQSB <dbl>,

# SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>, AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>,

# MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>, gt_GT_alleles <chr>R

# rows that don't have missing data in the IDV column

filter(variants, !is.na(IDV))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 101 × 29

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR25848… CP00… 4.33e5 NA CTTT… CTTT… 64 NA TRUE 12 1 12

2 SRR25848… CP00… 4.74e5 NA CCGC CCGC… 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9 10

3 SRR25848… CP00… 2.10e6 NA ACAG… ACAG… 56 NA TRUE 2 0.667 3

4 SRR25848… CP00… 2.33e6 NA AT ATT 167 NA TRUE 7 1 7

5 SRR25848… CP00… 3.90e6 NA A AC 43.4 NA TRUE 2 1 2

6 SRR25848… CP00… 4.43e6 NA TGG T 228 NA TRUE 10 1 10

7 SRR25848… CP00… 1.48e5 NA AGGGG AGGG… 122 NA TRUE 8 1 8

8 SRR25848… CP00… 1.58e5 NA GTTT… GTTT… 19.5 NA TRUE 6 1 6

9 SRR25848… CP00… 1.73e5 NA CAA CA 180 NA TRUE 11 1 11

10 SRR25848… CP00… 1.75e5 NA GAA GA 194 NA TRUE 10 1 10

# ℹ 91 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>, MQSB <dbl>,

# SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>, AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>,

# MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>, gt_GT_alleles <chr>We have a column titled “QUAL”. This is a Phred-scaled confidence

score that a polymorphism exists at this position given the sequencing

data. Lower QUAL scores indicate low probability of a polymorphism

existing at that site. filter() can be useful for selecting

mutations that have a QUAL score above a certain threshold:

R

# rows with QUAL values greater than or equal to 100

filter(variants, QUAL >= 100)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 666 × 29

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR25848… CP00… 2.82e5 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA 10

2 SRR25848… CP00… 4.74e5 NA CCGC CCGC… 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9 10

3 SRR25848… CP00… 6.49e5 NA C T 210 NA FALSE NA NA 10

4 SRR25848… CP00… 1.33e6 NA C A 178 NA FALSE NA NA 8

5 SRR25848… CP00… 1.73e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 11

6 SRR25848… CP00… 2.33e6 NA AT ATT 167 NA TRUE 7 1 7

7 SRR25848… CP00… 2.41e6 NA A C 104 NA FALSE NA NA 9

8 SRR25848… CP00… 2.45e6 NA A C 225 NA FALSE NA NA 20

9 SRR25848… CP00… 2.67e6 NA A T 225 NA FALSE NA NA 19

10 SRR25848… CP00… 3.00e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 15

# ℹ 656 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>, MQSB <dbl>,

# SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>, AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>,

# MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>, gt_GT_alleles <chr>filter() allows you to combine multiple conditions. You

can separate them using a , as arguments to the function,

they will be combined using the & (AND) logical

operator. If you need to use the | (OR) logical operator,

you can specify it explicitly:

R

# this is equivalent to:

# filter(variants, sample_id == "SRR2584863" & QUAL >= 100)

filter(variants, sample_id == "SRR2584863", QUAL >= 100)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 19 × 29

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR25848… CP00… 2.82e5 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA 10

2 SRR25848… CP00… 4.74e5 NA CCGC CCGC… 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9 10

3 SRR25848… CP00… 6.49e5 NA C T 210 NA FALSE NA NA 10

4 SRR25848… CP00… 1.33e6 NA C A 178 NA FALSE NA NA 8

5 SRR25848… CP00… 1.73e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 11

6 SRR25848… CP00… 2.33e6 NA AT ATT 167 NA TRUE 7 1 7

7 SRR25848… CP00… 2.41e6 NA A C 104 NA FALSE NA NA 9

8 SRR25848… CP00… 2.45e6 NA A C 225 NA FALSE NA NA 20

9 SRR25848… CP00… 2.67e6 NA A T 225 NA FALSE NA NA 19

10 SRR25848… CP00… 3.00e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 15

11 SRR25848… CP00… 3.34e6 NA A C 211 NA FALSE NA NA 10

12 SRR25848… CP00… 3.40e6 NA C A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 14

13 SRR25848… CP00… 3.48e6 NA A G 200 NA FALSE NA NA 9

14 SRR25848… CP00… 3.49e6 NA A C 225 NA FALSE NA NA 13

15 SRR25848… CP00… 3.91e6 NA G T 225 NA FALSE NA NA 10

16 SRR25848… CP00… 4.10e6 NA A G 225 NA FALSE NA NA 16

17 SRR25848… CP00… 4.20e6 NA A C 225 NA FALSE NA NA 11

18 SRR25848… CP00… 4.43e6 NA TGG T 228 NA TRUE 10 1 10

19 SRR25848… CP00… 4.62e6 NA A C 185 NA FALSE NA NA 9

# ℹ 17 more variables: VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>, MQSB <dbl>,

# SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>, AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>,

# MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>, gt_GT_alleles <chr>R

# using `|` logical operator

filter(variants, sample_id == "SRR2584863", (MQ >= 50 | QUAL >= 100))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 23 × 29

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR2584863 CP000819… 9.97e3 NA T G 91 NA FALSE NA NA

2 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.82e5 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA

3 SRR2584863 CP000819… 4.33e5 NA CTTT… CTTT… 64 NA TRUE 12 1

4 SRR2584863 CP000819… 4.74e5 NA CCGC CCGC… 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9

5 SRR2584863 CP000819… 6.49e5 NA C T 210 NA FALSE NA NA

6 SRR2584863 CP000819… 1.33e6 NA C A 178 NA FALSE NA NA

7 SRR2584863 CP000819… 1.73e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA

8 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.10e6 NA ACAG… ACAG… 56 NA TRUE 2 0.667

9 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.33e6 NA AT ATT 167 NA TRUE 7 1

10 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.41e6 NA A C 104 NA FALSE NA NA

# ℹ 13 more rows

# ℹ 18 more variables: DP <dbl>, VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>,

# MQSB <dbl>, SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>,

# AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>, MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>,

# gt_GT_alleles <chr>Challenge

Select all the mutations that occurred between the positions 1e6 (one million) and 2e6 (inclusive) that have a QUAL greater than 200, and exclude INDEL mutations. Hint: to flip logical values such as TRUE to a FALSE, we can use to negation symbol “!”. (eg. !TRUE == FALSE).

R

filter(variants, POS >= 1e6 & POS <= 2e6, QUAL > 200, !INDEL)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 77 × 29

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR25848… CP00… 1.73e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA 11

2 SRR25848… CP00… 1.00e6 NA A G 225 NA FALSE NA NA 15

3 SRR25848… CP00… 1.02e6 NA A G 225 NA FALSE NA NA 12

4 SRR25848… CP00… 1.06e6 NA C T 225 NA FALSE NA NA 17

5 SRR25848… CP00… 1.06e6 NA A G 206 NA FALSE NA NA 9

6 SRR25848… CP00… 1.07e6 NA G T 225 NA FALSE NA NA 11

7 SRR25848… CP00… 1.07e6 NA T C 225 NA FALSE NA NA 12

8 SRR25848… CP00… 1.10e6 NA C T 225 NA FALSE NA NA 15

9 SRR25848… CP00… 1.11e6 NA C T 212 NA FALSE NA NA 9

10 SRR25848… CP00… 1.11e6 NA A G 225 NA FALSE NA NA 14

# ℹ 67 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>, MQSB <dbl>,

# SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>, AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>,

# MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>, gt_GT_alleles <chr>Pipes

But what if you wanted to select and filter? We can do this with

pipes. Pipes let you take the output of one function and send it

directly to the next, which is useful when you need to many things to

the same data set. It was possible to do this before pipes were added to

R, but it was much messier and more difficult. Pipes in R look like

%>% and are made available via the magrittr

package, which is installed as part of dplyr. If you use

RStudio, you can type the pipe with Ctrl + Shift +

M if you’re using a PC, or Cmd + Shift

+ M if you’re using a Mac.

R

variants %>%

filter(sample_id == "SRR2584863") %>%

select(REF, ALT, DP)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 25 × 3

REF ALT DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 T G 4

2 G T 6

3 G T 10

4 CTTTTTTT CTTTTTTTT 12

5 CCGC CCGCGC 10

6 C T 10

7 C A 8

8 G A 11

9 ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAG ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGC… 3

10 AT ATT 7

# ℹ 15 more rowsIn the above code, we use the pipe to send the variants

data set first through filter(), to keep rows where

sample_id matches a particular sample, and then through

select() to keep only the REF,

ALT, and DP columns. Since %>%

takes the object on its left and passes it as the first argument to the

function on its right, we don’t need to explicitly include the data

frame as an argument to the filter() and

select() functions any more.

Same code with no pipes

Without pipes the code would look like the following.

R

select(filter(variants, sample_id == "SRR2584863"), REF, ALT, DP)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 25 × 3

REF ALT DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 T G 4

2 G T 6

3 G T 10

4 CTTTTTTT CTTTTTTTT 12

5 CCGC CCGCGC 10

6 C T 10

7 C A 8

8 G A 11

9 ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAG ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGC… 3

10 AT ATT 7

# ℹ 15 more rowsIn this code we do the filter first and then wrap the

select function around it to use the output of the

filter command as the input fo the select

function. While both are valid, using pipes is considered more readable

as it displays the functions in top down order, instead of inside out

order.

Some may find it helpful to read the pipe like the word “then”. For

instance, in the above example, we took the data frame

variants, then we filtered for rows

where sample_id was SRR2584863, then we

selected the REF, ALT, and

DP columns. The dplyr

functions by themselves are somewhat simple, but by combining them into

linear workflows with the pipe, we can accomplish more complex

manipulations of data frames.

If we want to create a new object with this smaller version of the data we can do so by assigning it a new name:

R

SRR2584863_variants <- variants %>%

filter(sample_id == "SRR2584863") %>%

select(REF, ALT, DP)

This new object includes all of the data from this sample. Let’s look at just the first six rows to confirm it’s what we want:

R

SRR2584863_variants

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 25 × 3

REF ALT DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 T G 4

2 G T 6

3 G T 10

4 CTTTTTTT CTTTTTTTT 12

5 CCGC CCGCGC 10

6 C T 10

7 C A 8

8 G A 11

9 ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAG ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGC… 3

10 AT ATT 7

# ℹ 15 more rowsWe can use the head() and tail() functions

to look at the first or last six rows. There is also a more versitle

tidyverse function slice(), that allows users to specify a

range to view:

R

SRR2584863_variants %>% head()

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 6 × 3

REF ALT DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 T G 4

2 G T 6

3 G T 10

4 CTTTTTTT CTTTTTTTT 12

5 CCGC CCGCGC 10

6 C T 10R

SRR2584863_variants %>% tail()

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 6 × 3

REF ALT DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 A AC 2

2 G T 10

3 A G 16

4 A C 11

5 TGG T 10

6 A C 9R

SRR2584863_variants %>% slice(4:10) # shows rows 4-10 instead

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 7 × 3

REF ALT DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 CTTTTTTT CTTTTTTTT 12

2 CCGC CCGCGC 10

3 C T 10

4 C A 8

5 G A 11

6 ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAG ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCC… 3

7 AT ATT 7Exercise: Pipe and filter

Starting with the variants data frame, use pipes to

subset the data to include only observations from SRR2584863 sample,

where the filtered depth (DP) is at least 10. Showing only 5th through

11th rows of columns REF, ALT, and

POS.

R

variants %>%

filter(sample_id == "SRR2584863" & DP >= 10) %>%

slice(5:11) %>%

select(sample_id, DP, REF, ALT, POS)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 7 × 5

sample_id DP REF ALT POS

<chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 SRR2584863 11 G A 1733343

2 SRR2584863 20 A C 2446984

3 SRR2584863 12 G T 2618472

4 SRR2584863 19 A T 2665639

5 SRR2584863 15 G A 2999330

6 SRR2584863 10 A C 3339313

7 SRR2584863 14 C A 3401754Mutate

Frequently you’ll want to create new columns based on the values in

existing columns, for example to do unit conversions or find the ratio

of values in two columns. For this we’ll use the dplyr

function mutate().

For example, we can convert the polymorphism confidence value QUAL to a probability value according to the formula:

Probability = 1- 10 ^ -(QUAL/10)

We can use mutate to add a column (POLPROB)

to our variants data frame that shows the probability of a

polymorphism at that site given the data.

R

variants %>%

mutate(POLPROB = 1 - (10 ^ -(QUAL/10)))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 801 × 30

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR2584863 CP000819… 9.97e3 NA T G 91 NA FALSE NA NA

2 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.63e5 NA G T 85 NA FALSE NA NA

3 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.82e5 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA

4 SRR2584863 CP000819… 4.33e5 NA CTTT… CTTT… 64 NA TRUE 12 1

5 SRR2584863 CP000819… 4.74e5 NA CCGC CCGC… 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9

6 SRR2584863 CP000819… 6.49e5 NA C T 210 NA FALSE NA NA

7 SRR2584863 CP000819… 1.33e6 NA C A 178 NA FALSE NA NA

8 SRR2584863 CP000819… 1.73e6 NA G A 225 NA FALSE NA NA

9 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.10e6 NA ACAG… ACAG… 56 NA TRUE 2 0.667

10 SRR2584863 CP000819… 2.33e6 NA AT ATT 167 NA TRUE 7 1

# ℹ 791 more rows

# ℹ 19 more variables: DP <dbl>, VDB <dbl>, RPB <dbl>, MQB <dbl>, BQB <dbl>,

# MQSB <dbl>, SGB <dbl>, MQ0F <dbl>, ICB <lgl>, HOB <lgl>, AC <dbl>,

# AN <dbl>, DP4 <chr>, MQ <dbl>, Indiv <chr>, gt_PL <dbl>, gt_GT <dbl>,

# gt_GT_alleles <chr>, POLPROB <dbl>Note, we did not save the new column. We printed the resulting data

frame to the screen. If we want to save the data frame with the new

column, we need to assign it to an object, either overwriting our

variants object (which could be risky of a column of the

same name exists) or creating a new object to store it (which takes up

more space). You will need to think carefully about how to structure

your objects in R.

Exercise

- There are a lot of columns in our data set, so let’s just look at

the

sample_id,POS,QUAL, andPOLPROBcolumns for now. 1. Add a line to the above code to only show those columns. - Sometimes we may want to order the result by a column, perhaps to

have the highest values at the top. Look at the help page for

arrange()and see if you can make the highest values at the top of the resulting data frame. What would you do if you wanted the lowest values at the top?

R

variants %>%

mutate(POLPROB = 1 - 10 ^ -(QUAL/10)) %>%

select(sample_id, POS, QUAL, POLPROB) %>% # part 1

arrange(POLPROB) # part 2

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 801 × 4

sample_id POS QUAL POLPROB

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR2584866 2055833 4.38 0.636

2 SRR2584866 3538863 4.95 0.680

3 SRR2584866 3550069 5.05 0.687

4 SRR2584866 3550071 5.05 0.687

5 SRR2584866 634603 5.61 0.725

6 SRR2584866 2055692 5.76 0.734

7 SRR2584866 1424975 7.45 0.820

8 SRR2584866 942702 7.91 0.838

9 SRR2584866 2055662 8.14 0.846

10 SRR2584866 1746738 8.38 0.855

# ℹ 791 more rowsHow can you make the lowest values on the top? Add the

desc() function.

R

variants %>%

mutate(POLPROB = 1 - 10 ^ -(QUAL/10)) %>%

select(sample_id, POS, QUAL, POLPROB) %>%

arrange(desc(POLPROB))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 801 × 4

sample_id POS QUAL POLPROB

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR2584863 281923 217 1

2 SRR2584863 473901 228 1

3 SRR2584863 648692 210 1

4 SRR2584863 1331794 178 1

5 SRR2584863 1733343 225 1

6 SRR2584863 2333538 167 1

7 SRR2584863 2446984 225 1

8 SRR2584863 2665639 225 1

9 SRR2584863 2999330 225 1

10 SRR2584863 3339313 211 1

# ℹ 791 more rowsgroup_by() and summarize() functions

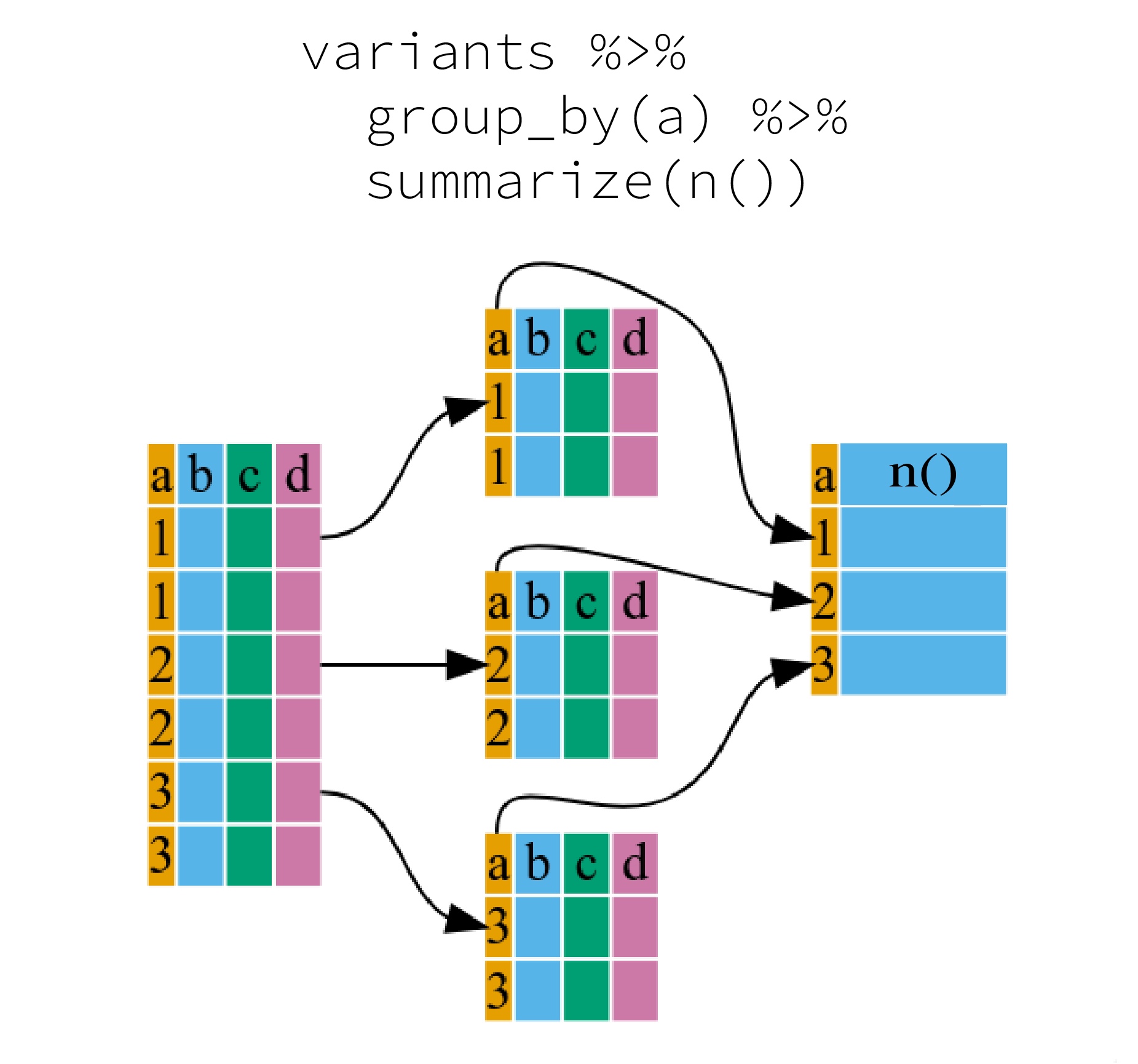

Many data analysis tasks can be approached using the

“split-apply-combine” paradigm: split the data into groups, apply some

analysis to each group, and then combine the results. dplyr

makes this very easy through the use of the group_by()

function, which splits the data into groups.

We can use group_by() to tally the number of mutations

detected in each sample using the function tally():

R

variants %>%

group_by(sample_id) %>%

tally()

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 2

sample_id n

<chr> <int>

1 SRR2584863 25

2 SRR2584866 766

3 SRR2589044 10Since counting or tallying values is a common use case for

group_by(), an alternative function was created to bypasses

group_by() using the function count():

R

variants %>%

count(sample_id)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 2

sample_id n

<chr> <int>

1 SRR2584863 25

2 SRR2584866 766

3 SRR2589044 10Challenge

- Count how many mutations are INDELS vs substitutions (aka not indels).

- Hint: INDELS is TRUE/FALSE column in the data.

R

variants %>%

count(INDEL)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 2 × 2

INDEL n

<lgl> <int>

1 FALSE 700

2 TRUE 101When the data is grouped, summarize() can be used to

collapse each group into a single-row summary. summarize()

does this by applying an aggregating or summary function to each

group.

It can be a bit tricky at first, but we can imagine physically splitting the data frame by groups and applying a certain function to summarize the data.

We can also apply many other functions to individual columns to get

other summary statistics. For example,we can use built-in functions like

mean(), median(), min(), and

max(). These are called “built-in functions” because they

come with R and don’t require that you install any additional packages.

By default, all R functions operating on vectors that contains

missing data will return NA. It’s a way to make sure that users

know they have missing data, and make a conscious decision on how to

deal with it. When dealing with simple statistics like the mean, the

easiest way to ignore NA (the missing data) is to use

na.rm = TRUE (rm stands for remove).

So to view the mean, median, maximum, and minimum filtered depth

(DP) for each sample:

R

variants %>%

group_by(sample_id) %>%

summarize(

mean_DP = mean(DP),

median_DP = median(DP),

min_DP = min(DP),

max_DP = max(DP))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 5

sample_id mean_DP median_DP min_DP max_DP

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 SRR2584863 10.4 10 2 20

2 SRR2584866 10.6 10 2 79

3 SRR2589044 9.3 9.5 3 16Grouped Data Frames in Tidyverse

When you group a data frame with group_by(), you get a

grouped data frame. This is a special type of data frame that has all

the properties of a regular data frame but also has an additional

attribute that describes the grouping structure. The primary advantage

of a grouped data frame is that it allows you to work with each group of

observations as if they were a separate data frame.

Operations like summarise() and mutate()

will be applied to each group separately. This is particularly useful

when you want to perform calculations on subsets of your data.

To remove the grouping structure from a grouped data frame, you can

use the ungroup() function. This will return a regular data

frame.

For more details, refer to the dplyr documentation on grouping.

Combining data frames

There are times you may have multiple data tables that have information that could come together in them. This is often a structure set up that reflects database management where you you separate out different information into different related tables. For example, you may have one table that contains the results from your SNP analysis, as we have been using in this lesson, and another that has the metadata about your samples. For some applications you may want to pull information from that metadata table and be able to use it in your SNP analysis, maybe particular groupings that are repsented in the metadata table or alternate names, or other information.

For our example, we want to be able to use the generation number

instead of the sample_id for further analyses and perhaps

plotting later. We have a table of metadata from the Project

Organization and Management for Genomics lesson that includes

columns that matches up the sample_id column with the

generation information.

First, we will download the metadata table using the

download.file function in R.

R

download.file("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/datacarpentry/wrangling-genomics/gh-pages/files/Ecoli_metadata_composite.tsv", destfile = "data/Ecoli_metadata_composite.tsv")

We will only need to do this once and not every time we run our script so we can then comment the last line out.

Next we need to load the metadata table into an object in R. This

time we will use the read_delim() function as it has preset

arguments that work well for tab separated value files,

tsv, which is the format this table is

R

metadata <- read_delim("data/Ecoli_metadata_composite.tsv")

WARNING

Warning: One or more parsing issues, call `problems()` on your data frame for details,

e.g.:

dat <- vroom(...)

problems(dat)This prints a warning message because the last entry is missing some values but it should still work for our purposes.

Before we match-up our table, we will simplify the metadata table to only include 3 columns.

R

metadata_sub <- select(metadata, strain, generation, run)

Now we need to consider how we want to merge these two tables together. There are many ways we might intersect these two tables, for example: Do we want an intersection that only keeps rows that match in a certain column from both tables? Do we want to keep only the rows from one table and the matching information from the other table? Do we want to keep only the non-matching information from both tables (though this is less common)?

In our case we want to keep all the rows from the

variants table and then pull information that matches from

the metadata_sub table. First, we will explore what happens

when we join these tables in other ways as well as an experiment.

First we will try to keep only the rows, observations, that match in

both tables. This is called an inner_join. For this join we

need to tell it which columns are equivalent in our two data frames. You

will not need to do this if the columns have the same name across data

frames but in our case what is called sample_id in the

variants data frame is called run in the

metadata_sub data frame.

R

inner <- inner_join(variants, metadata_sub, by = join_by(sample_id == run))

In this case the inner data frame is the same number of

rows (801) as the variants data frame. This is because all

of the sample_id’s that are in the variants

data frame have a corresponding run in

metadata_sub. If one was missing, then all of the data for

that sample would be dropped from the resulting data frame.

We can also see that instead of having 29 columns/variables like

variants, inner has 31 columns/variables. You

may want to run View(inner) and scroll to the far right to

see the new strain, and generation columns

that were added from the metadata_sub table. Note, it did

not add on the run column since that is repeated

information in the sample_id column. Also, we would have

had many more new columns added if we had used the full

metadata data frame instead of the

metadata_sub data frame.

Next we will try an “outer join” which only keeps all observations which are present in either data frames.

R

full <- full_join(variants, metadata_sub, by = join_by(sample_id == run))

The new full data frame now has more rows than

inner or variants! Though it has the same

number of columns as inner adding on the two additional

strain and generation columns. Why do you

think this has more rows than our original data? Hint: You may want

to View(full) and scroll down to the botton of the data

frame.

Once you look at the bottom of the data frame, you will see a bunch

of sample_id’s that we did not run the SNP analysis on but

were in the metadata_sub data frame. The full join will

keep every unique observation from your by columns even if

they do not match up in the other table.

This isn’t quite what we were looking for either.

What we want is to keep all the data in our variants

data frame, even if we do not find a match for it in the

metadata_sub table, so we avoid dropping any data if the

metadata_sub is missing some information. In this case we

will instead use another “outer join” option called “left join”. A left

join keeps all of the data in the table written on the left side of our

function, and will add on columns where the table on the right side

matches via our by statement.

R

# arguments "left tbl" "right tbl"

left <- left_join(variants, metadata_sub, by = join_by(sample_id == run))

In this case, the resulting data frame matches our inner

result exactly because there was no missing data in our right table.

Note: A “right” join is the opposite of a “left” so it will keep all the

data in the right most listed table and merge on the info in the left

most listed table

It is important to think carefully about what kind of join you want and check the resulting data frames to make sure they are what you expected when you planned your join. In this case, our “inner” and “left” join are the same but you want to be careful about possibly dropping or duplicating data depending on how the data frames are structured.

Finally, we can now do a data manipulation using the

generation column instead of the sample_id

column. We can repeat the calculations for counting SNPs for each

sample

R

left %>%

count(generation)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 2

generation n

<dbl> <int>

1 5000 10

2 15000 25

3 50000 766This result makes it easier to see the accumulation of more SNPs at later generations, without us having to know the sample IDs.

What about right joins?

- How many rows and columns would you expect from the following right join?

right_join(variants, metadata_sub, by = join_by(sample_id == run))

- How many rows and columns would you expect from the following right join?

right_join(metadata_sub, variants, by = join_by(run == sample_id))

Think carefully about the data in question and which data frame is on the right and which is on the left.

Part 1 There will be 860 rows and 31 variables, just

like the full join. All of the sample_id’s in the

variants data frame have matches and will be kept and then

it will also add on the run values that do not match but

were represented in the metadata_sub data frame with empty

info in the other columns since there is no matching rows in the

variants data frame.

Part 2 There will be 801 rows and 31 variables, just

like the inner and left joins. This join should always match exactly the

left join as it is the mirrored right join. It will only match the inner

join if all of the samples in the by match-up in the right

data frame are in the left data frame as well, otherwise it will drop

the rows not listed in the left for the inner join.

Reshaping data frames - Extra

It can sometimes be useful to transform the “long” tidy format, into

the wide format. This transformation can be done with the

pivot_wider() function provided by the tidyr

package (also part of the tidyverse).

pivot_wider() takes a data frame as the first argument,

and two arguments: the column name that will become the columns and the

column name that will become the cells in the wide data.

R

variants_wide <- variants %>%

group_by(sample_id, CHROM) %>%

summarize(mean_DP = mean(DP)) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = sample_id, values_from = mean_DP)

OUTPUT

`summarise()` has grouped output by 'sample_id'. You can override using the

`.groups` argument.R

variants_wide

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 4

CHROM SRR2584863 SRR2584866 SRR2589044

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 CP000819.1 10.4 10.6 9.3The opposite operation of pivot_wider() is taken care by

pivot_longer(). We specify the names of the new columns,

and here add -CHROM as this column shouldn’t be affected by

the reshaping:

R

variants_wide %>%

pivot_longer(-CHROM, names_to = "sample_id", values_to = "mean_DP")

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 3

CHROM sample_id mean_DP

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 CP000819.1 SRR2584863 10.4

2 CP000819.1 SRR2584866 10.6

3 CP000819.1 SRR2589044 9.3Resources

- Use the

dplyrpackage to manipulate data frames. - Use

glimpse()to quickly look at your data frame. - Use

select()to choose variables from a data frame. - Use

filter()to choose data based on values. - Use

mutate()to create new variables. - Use

group_by()andsummarize()to work with subsets of data.

The figure was adapted from the Software Carpentry lesson, R for Reproducible Scientific Analysis↩︎